Communication Theology: Some Considerations

By Franz-Josef Eilers, SVD

[The late Father Eilers was the Co-Founder and Executive Director of the Asian Research Center for Religion and Social Communication (ARC) at St. John’s University in Bangkok, Thailand. His death was a great loss to Social Communication and Theology research and study.]

It should be clear right from the beginning that communication is more than just Media or even Mass Media. They are part of social communication, but finally, only a part. Since Vatican II we are used in Church circles – and in a growing way beyond – to talk about Social Communication. When the preparatory Commission for the Vatican II decree on Social Communication, Inter Mirifica, proposed this expression they argued expressions like Mass Media, Media of Diffusion, Audio-Visual means or similar designations would not sufficiently express what the Church is concerned about. Therefore, they proposed the new name Social Communication referring to the communication of, and in, human society and thus including all ways and means of communicating within a community.

Italian scholar Giorgio Braga explains that Social Communication is “the study of communicative processes within Society.” Thus, Social Communication is concerned about the “interactions of human beings in their public expressions within a respective society or cultural group.” Pope John Paul II describes all this in his World Communication Message for 1992 when he writes: “We celebrate the blessings of speech, of hearing, of sight, which enable us to emerge from our isolation and loneliness to exchange with those around us the thoughts and sentiments which arise in our hearts. We celebrate the gifts of writing and reading, by which the wisdom of our ancestors is placed at our disposal, and our own experience and reflection are passed on to the generations that follow us. Then…we recognize the value of the ‘marvels’ even more wonderful: the ‘marvels of technology which God has destined human genius to discover’ (Inter Mirifica 1) …” Communication Theology must be seen based upon this background.

Communication as Theological Concept

The German theologian Gisbert Greshake has convincingly shown that the expression and concept of Communication is, right from its beginning, theological. He maintains “Communication is, from its origin, a decisively theological idea, based especially in Christian revelation, and it expresses the center of the Christian understanding of God and world.” (2002, 6) Before the expression becomes a theological concept, however, it grounds itself on the common use of the word including its philosophical meaning. In this understanding, the expression originates in two connotations which interrelate:

The radix of the word communication rests in mun which means something like threshold, circumscription, within something (“intramuros”), thus implying a common room/place for living, where everybody depends on everybody. Thus, it refers to a common ‘room’ for living.

The other connotation refers to the Latin word munus, gift: the one who communicates passes on a ‘gift’ which, this way, also leads to communion.

Both meanings show that communication is a process of mutual giving…The philosophical use of communion/communication (‘Koinonia’) must be added, beginning with the axiom of Pythagoras: ‘between friends, everything is common’ which later, in Neo-Platonian understanding, leads to the Latin expression: “Bonum est communicativum et diffusivum sui.” (2002,8) The highest expression of this old philosophical concept is God himself. As Proclos said: “All unity is formed after the one, and all plurality somehow participates in the One.” For Greshake this builds the foundation for a Trinitarian God who communicates Himself in Jesus of Nazareth in the power of the Holy Spirit. He does not communicate something but himself. The presence of Jesus Christ is the self-communication of God to human beings. Without further following Greshake, this brings us right into further considerations on Communication Theology.

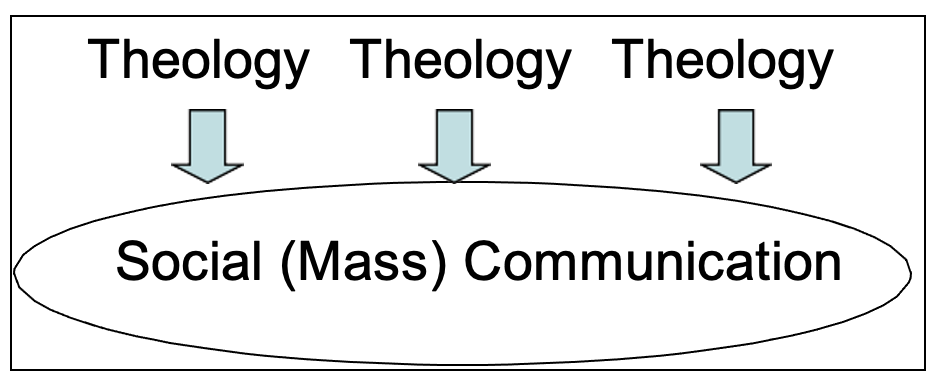

Differences in Perspective

We must first start with some clarifying distinctions. Over many years, we have talked about a Theology of Communication which is not really reflected in Greshake’s considerations. To me, this somehow appears as an attempt to ‘baptize’ the (mass) media: Today we have these modern means - as St. Arnold Janssen said at the opening of his first owned printing press in Steyl 1876 - and we must use them as God’s gift. In this understanding, media are seen as instruments to be used for the kingdom of God. Such understanding is underlying many Church documents until today. Even the Pontifical Council for Social Communication was originally the “Commission for the Instruments of Social Communication”.

In fact, such an approach can already be seen soon after Gutenberg’s invention of movable letters for printing which introduced a new era of modern communication. From a total number of 498 new titles published in German speaking countries in 1523, six years after the Reformation, 418 were from Protestant authors. From Luther’s treaty on indulgences some 1,500 copies were sold within a few days at the autumn Trade Fair in Frankfurt in 1518, one year after the begin of Reformation. (cf. Eilers 2002, 66). Theology of Communication meant using media and other means of communication for theological purposes even in the early times of the modern age.

Such attempts to ‘theologize’ Communication can hardly be sufficient for a communication which must be considered as an essential element of the Church.

Another way to look at communication under a theological perspective is reflected in Communicative Theology. This is an attempt to make theology and theological considerations better understandable using words, expressions and means to be easily understood by the recipients. Theology expresses itself in an easily understandable ‘language.’ Already Luther’s Bible translation into understandable German language goes in this direction though, even before him, other German translations of the Bible did exist. In a recent development in German speaking countries, this expression is also used for a theology which grows from spiritual and theological experiences of Christian communities. This is like liberation theology which in theologizing starts with the life of the people.

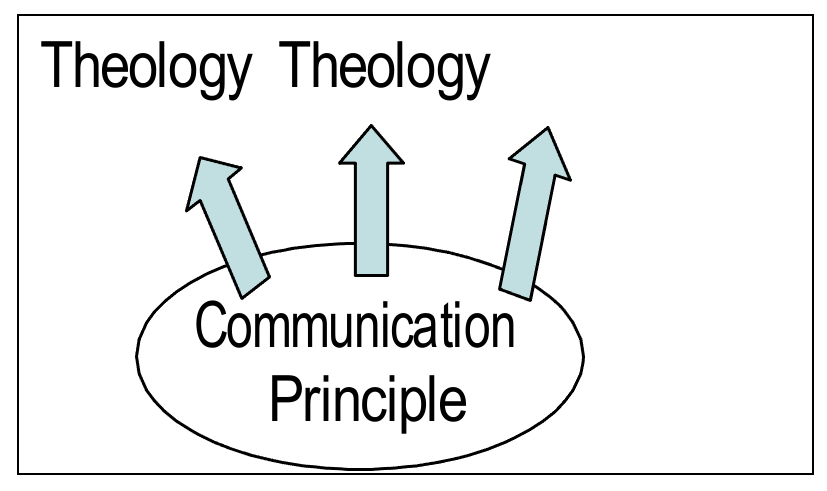

Karl Rahner made God’s Self-Communication a key concept of Theology (Rahner 1961, 333; 1969, 522ff.) He maintains God communicates himself as a person, being gift and giver at the same time, as the personification of love (“Deus Caritas est” 1 John 4,8). The origin of the world, the basic aim and content of history, and her final fulfillment, originate in the Self-Communication of God. From this Peter Henrici, the first director of the “Centro Interdisciplinare sulla Communicazione Sociale” at the Gregorian University in Rome, points to the fact (1986) that the relation between Theology and Communication could not be one of the so called “Genitive Theologies” but rather communication should be an inner structural principle of the whole of Theology. Such a perspective continues Rahner’s view; Gods’ Self-Communication is a key concept for the whole of Theology. Thus, Communication Theology does not start with media, or technical means but, rather, with the center of theology, with God himself. Communication does become the eye through which the whole of theology is seen because the Christian God is a communicating God. Communication becomes a theological principle, a perspective under which the whole of theology is seen.

Avery Dulles (1969) points to this when he says that “theology is, at every point, concerned with the realities of communication” -- confirming that Karl Rahner “brings out the communications dimension” of theology. This is true especially with what he calls “symbolic communication.” In fact, Dulles shows the consequences of this in a chapter on “Theology and Symbolic Communication” with special sections on Fundamental and Practical, but also Systematic Theology. According to him this is also reflected in a special way in fields like Christology, Creation, Grace, Sacraments, Ecclesiology and Eschatology.

Juergen Werbick (1997,214 f.) points to this in the section on Communication in volume 11 of the dictionary for Theology and Church (“Lexikon fuer Theologie und Kirche”). He is saying that communication is, for some 30 years, a leading perspective for fundamental theology where revelation, faith, tradition, and ecclesiastical practice are grounded on communicative realities. “God reveals himself in a communicative way, i.e. He shares Himself to humans in a relationship which is based on a dialogic exchange of word and response (“Wort und Antwort”), a partnership (“Covenant”), which enables a new communicative culture.”

Here, Christian faith and practice respond to God’s communicating love as revealed by Jesus Christ. Communication thus, becomes a theological principle under which the whole of theology is considered and studied. The main elements of such a Communication Theology are Trinity, Revelation, Incarnation and, finally, the Church.

Trinity

At the beginning of Communication Theology stands a Trinitarian God who, within Himself, is Communication. Jesus Christ revealed to us a communicating Trinitarian God. There is an ongoing communication between the Father and the Son in the Holy Spirit as the Latin-American Bishops said in their statement of the Puebla Assembly (1976):

Christ reveals to us that divine life is Trinitarian communion. Father, Son and Spirit live in the supreme mystery of oneness in perfect, loving intercommunion. It is the source of all love and all communion that gives dignity and grandeur to human existence.”

Carlo Martini in his pastoral plan on Communication for the archdiocese of Milan “Ephata, Apriti” refers to the different scriptural sources for this and concludes: “From the Gospel words transpires that sense of profound communion and exchange which live in the mystery of God and which is at the root of all our human communication.” In the Trinitarian communion, the dialogue between the persons is ongoing. We can say that in the Trinity the three Divine persons are the more persons as they form a unified communion and the more communion as they are persons. This way each one of us realizes the same, the more he lives the appropriate identity in dialogue and as gift with, and through, others.

Bernhard Haering (1979, 46) is also quoted by Dulles in summarizing this mystery in the following way: “Communication is constitutive in the mystery of God. Each of the three Divine Persons possesses all that is good, all that is true, all that is beautiful, but in the modality of communion and communication. Creation, redemption, and communication arise from this mystery and have as their final purpose to draw us, by this very communication, into communion with God. Creating us in His image and likeness, God makes us sharers of his creative and liberating communication in communion, through communion, and in view of communion.” As human beings, we can communicate because we are created in the image and likeness of such a communicating Trinitarian God!

This communication perspective was also reflected in Asia when Pope John Paul II in his Apostolic Exhortation Ecclesia in Asia (1999) wrote “Communion and Dialogue are two essential aspects of the Church’s mission, which have their infinitely transcendent exemplar in the mystery of the Trinity, from whom all mission comes and to whom it must be re-directed.” (No.31)

This understanding leads then to the next dimension of Communication Theology, Revelation.

Revelation

Gisbert Greshake in one of his books on Trinity (1999, 21f.) begins with the Trinitarian communication dimension for revelation which is not only notional but the experience of God’s personal self-revelation to his creatures. He writes:

To the Christian understanding of revelation belongs a threefold consideration:

It is the infinite God the Father who reveals himself without limits to humans to unite himself with them in the closest community of love.

This revelation happens in the Word –in the broad sense – in a fully human way so we are all able to understand. At the high point of this God’s revelation, the Word appears in Jesus Christ – God’s Son becoming man in whom God expresses and gives himself totally and without reservation.

The acceptance and understanding of God’s word occurs within man in a divine way which means the personal, subjective acceptance of God’s word happens in the power of God acting in the Holy Spirit.

Only if all these three elements come together can one realize without contradiction that God does not reveal something about him but rather that he communicates himself, literally, in infinite love, and shelters the human beings into his divine life. Revelation understood as radical self-communication therefore presupposes a Trinitarian understanding of God.

The Vatican II Constitution on Revelation, Dei Verbum, states: “By Divine Revelation God wished to manifest and communicate both himself and the eternal decrees of his will for the salvation of mankind. He wished, in other words, to share with us divine benefits which entirely surpass the powers of human mind to understand.” (No.6) Evangelii Nuntiandi (1975, No. 42) speaks of the word as “the bearer of the power of God.” Thus, Christian Communication, in its revelatory aspect, becomes a saving power. God’s revelation is not just a passing on of ‘information’ in its narrow sense; it is indeed a dialogic process with concrete effects in life, manifested in the sacraments.

The dialogic process of Revelation builds on the general means of, and for, human communication. God’s revelation and communication takes place through all the human senses as St. John expresses in his first letter (1 John 1-3): “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands, concerning the Word of life … we proclaim also to you…” In his personal experience of conversion, St. Augustine shares how ‘revelation’ affected all his senses: “You called on me, you cried aloud to me, you broke my barrier of deafness. You shone upon me; your radiance enveloped me, you put my blindness to flight. You shed your fragrance about me; I drew breath and I gasp for your sweet odor. I tasted you and I hunger and thirst for you. You touched me and I am inflamed with love of your peace.” (X, 27) Both examples show how God’s revelation builds on human nature and experience. The “General Directory for Catechesis” from 1997 describes God as the one who “truly reveals himself, as one who desires to communicate himself, making the human person a participant in his Divine nature. In this way God accomplishes his plan of love.” (No.36)

Revelation is a divine, and at the same time human, communication happening. It is acting and re-acting. The human side, however, can reflect God’s perfect communication only in a limited way. Bernhard Haering reminds us that theology has to incorporate herself into the “rhythm of social communication of humankind and into the questions and language of the present world. To know the language of today’s people is thus a pre-condition for every Christian Communication. In passing on God’s revelation we also must respond to what the people ask. Hermeneutics is concerned with bringing the revelation and ‘word’ of history into the life of people now.” (1979, 46)

Biblical scholar Carlo Martini sees the following six criteria for God’s self- communication in revelation (1990, No. 30f; 58ff):

Divine Communication is prepared in Silence and in the secrecy of God. It is a “revelation of the mystery hidden for long ages past” (Rom.16, 25), it is a mystery “which for ages past was kept hidden in God, who created all things.” (Eph.3, 9)

God’s communication is progressive, cumulative, and historical. God’s self-communication to us is not realized in one instant, but rather, comprises different times with ups and downs. It happens in the situations of our world. His communication is realized through words and events reflected in the history of salvation as reported in the Bible which is the book of God’s Self-Communication and Self-Revelation.

Divine Communication realizes itself in the course of history in a dialectic way. This communication does not proceed from glory to glory in a light without shadow. There is, rather, a mixture of light and shadow and only a patient deciphering of words and events over time can lead to the full understanding of God’s communication.

God’s communication does not reach its fullness here on earth. One must distinguish between a communication in via and one in patria. All communication in history is incomplete in view of the final fullness of the Kingdom. It also means that in this world we never will know the other person totally the way s/he is. There will be always a secret, a reserve which cannot be fully clarified, even within ourselves.

Divine Communication is personal. God communicates Himself, not something else. He communicates out of himself as a sign and symbol of his will to communicate Himself as a supreme gift. Communication in revelation is, at the same time, inter-personal because He appeals to the human person who is to receive this gift. This calls for attention in reception and listening because without answer and feedback there is no real communication.

God’s communication, finally, assumes all ways and means of inter-personal communication. His communication is informative, appealing and, at the same time, self-communicating. He reveals himself in calling, threatening, admonishing, and loving.

God’s revelation continues until today, and beyond Christianity, as Vatican II says: God is not “remote from those who in shadows, and images seek the unknown God, since He gives all people life and breath and all things, and the Savior wills all to be saved … Whatever good and truth is found among them is considered by the Church to be a preparation for the Gospel and given by Him, who enlightens all people that they may have life.” (LG, 16) In this way revelation must also be seen as a preparation for the incarnating communication of Jesus Christ.

Incarnation

The incarnation of God’s son is the high point of Communication Theology. “In the past God communicated to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways; but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed heir of all things and through whom he made the universe. The son is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things by his powerful word.” (Hebr. 1, 1-3).

The Pastoral Instruction Communio et Progressio (1971,11), demanded by Vatican II, interprets this fact in saying:

While he was on earth Christ revealed himself as the perfect communicator. Through his incarnation, he utterly identified himself with those who were to receive his communication and he gave his message not only in words but in the whole manner of his life. He spoke from within, from the press of his people. He preached the Divine Message without fear and compromise. He adjusted to his people’s way of talking and to their pattern of thought. And he spoke out of the predicament of their time.

God’s incarnation through Jesus Christ is at the center of any Christian Communication. His son becoming one of us is the highest expression of communication which Communio et Progessio defines in its deepest sense as “giving of self in love.” (No. 11) It is quite revealing to reflect and study some of the ways and means of Jesus’ communication as reflected in scripture:

He speaks already through the circumstances of his life. His becoming flesh in the Holy Spirit, his birth in a manger, the hidden years in Nazareth, the 40 days in the desert, his suffering on Calvary, his death on the cross, and resurrection are powerful expressions of his mission and commitment from the Father.

The places where he preaches: He is the itinerant preacher, who communicates in synagogues and private houses, in the marketplace and streets, on the sea and the mountains Wherever he goes it is always in the service of his mission.

All of Jesus’ communication grounds in the sharing with the Father in prayer, especially at night and early morning before daily life starts again.

His speaking to people begins with their own daily experiences and concerns, which He brings into the will of the Father for the Kingdom. He never talks about himself but rather of the one who sent him. For this, He uses stories from daily life like the work of the fishermen, the sower, the experience of the widow searching for the lost coin.

His audiences are not only big crowds but also small groups, like his disciples, and he reaches out to individuals in deep personal sharing like Nicodemus, the Samaritan woman, Lazarus, and others.

His communication is embedded in the Scriptures of the First Testament, but he also uses parables and stories from daily life and even “News” like the death of those killed at the tower of Siloah.

His proclamation is not simple ‘entertainment.’ Jesus asks serious questions and confronts people. He demands decision making: “If your eye causes you…” “Do you also want to go?” He even puts people into crisis to force them to a decision.

All of Jesus’ healing is finally not just for healings’ sake but rather to re-establish the communication line with God the Father as Carlo Martini observes. Before the blindness of the eye is removed, sins are forgiven. “Your sins are forgiven” is more important than bodily health.

Jesus’ communication is not just passing on information and message. It reflects a deep personal commitment to the Father and his message demands the whole person. Jesus communicates with his whole being up to death on the cross. He goes far beyond just ‘talking’ which finally leads him to the silence on the cross, in the total commitment of his life.

Jesus’ communication is not finished in this life but points to a deeper reality beyond.

Mercy Seat

An artistic expression of the communicating God, which combines all these three steps, is the “Mercy Seat” (German: “Gnadenstuhl”). In this presentation, the Father gives his (suffering) Son in the Holy Spirit to humankind. Over the centuries, many presentations of different kinds have been created also by well-known artists like Albrecht Duerer and in the old mosaics of Ravenna. Carlo Martini sees them as the artistic expression of a communicating God. (1990, No. 4)

Mission

The Trinitarian self-communication of God in revelation and incarnation is continued until the end of time through the Church. It is her mission to continue God’s communication into the here and now of the present time. In fact, this communication is to be further unfolded under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, whom Jesus promises to the Church. It is to be lived especially in Kerygma, Koinonia and Diakonia.

The Mission document of Vatican II, Ad Gentes, sees Mission as the essence of the Church. In a similar way, Communication Theology sees communication at the center and as the essence of the Church. The Church exists to communicate. After all, Mission is also communicating. Further, the Church is a community, and no community can exist without communication. A theology of Communion presupposes a Communication Theology. Such communication is at the essence of the relation with God (vertical) but also presupposes communication on the horizontal level.

The emergence of modern technology for communication, from Gutenberg to the Internet, is a special gift to intensify, deepen, but also extend, this communication. “The Church would feel guilty before the Lord if she did not utilize these powerful means that human skill is daily rendering more perfect” (Evangelii Nuntiandi 1975, 45). The emergence of a “New Culture” (Redemptoris Missio 1990, 37c) which is determined by modern communications, therefore, is a special challenge but also an opportunity for the Church today. This goes far beyond any instrumentalization. A Communication Theology-based Ecclesiology is needed which includes also the new and emerging means of Information and Communication Technology (ICT).

The Second Vatican Council describes the communication obligation of the Church in the following words: “The one mediator, Christ, established and ever sustains here on earth His holy Church, the community of Faith, Hope and Charity, as a visible organization through which he communicates truth and grace to all people… For this reason, the Church is compared, not without significance, to the mystery of the incarnate Word.” (Lumen Gentium, 8) The Church as the body of Christ must “proclaim the Good News of the Kingdom of God” (Lc 4, 43) and she says with St. Paul: “Not that I boast of preaching the Gospel since it is a duty that has been laid on me; I should be punished if I did not preach it.” (1 Cor. 9, 16) Along these lines, the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi (1975) states that “Evangelizing – Communicating – is in fact the grace and vocation proper to the Church, her deepest identity. She exists to evangelize, that is in order to preach and teach, to be the channel of the gift of grace, to reconcile sinners with God and to perpetuate Christ’s sacrifice in the mass which is the memorial of his death and glorious resurrection” (No.14). Pope Paul VI reminds us in the same document that the Church acquires its “full meaning only when she becomes witness, when she evokes admiration and conversion and when it becomes the preaching and proclamation of the Good News” (No.15). Evangelii Nuntiandi sees as instruments of evangelization and communication, not only the mass media, but also other means, starting with the witness of life, followed by a living, preaching, liturgy, catechesis, personal contact, sacraments, and popular piety. (Nos.40-48).

Avery Dulles has analyzed the different documents of Vatican II under the perspective of Communication and the different Church models reflected in them. He comes up with the following models for a communicating Church:

The Institutional/Hierarchical Model “is narrowly concerned with the authority of the office and the obligatory character of official doctrine. It tends to view communication, in the theological sense, as a descending process beginning from God and passing through the papal and episcopal hierarchy to the other members of the Church…” (112) This model is concerned “with relationships within the Church between those who administer the Word and those to whom they minister…” It “makes a sharp distinction between the hierarchy as authoritative teacher (ecclesia docens,) and the rest of the faithful as learners (ecclesia discens).” Its “content is the Church’s authoritative teaching”. (114 f) Expressions of this model include official documents, pastoral letters, and announcements. It mainly refers to presentations in print.

The Herald or Kerygmatic Model is related by Dulles to Protestant biblical theology and Karl Barth’s theology of the Word but finds its expression especially in the Vatican document on Divine Revelation Dei Verbum and many parts of the decree on the missionary activity of the Church Ad Gentes. Following the mandate of Jesus, the Church “continues unceasingly to send heralds to proclaim the Gospel…” (114) Here, the communications ministry of the Church is seen as mainly serving the outside, whereas the first model concerns the inside communication of the Church. Since the Church by its nature, is missionary (Ad Gentes 2) “all baptized believers are bearers of the message.” This model responds in a special way to the oral dimensions of culture desiring finally the conversion of the hearers. In the hierarchical model, the response is “a submission of the intellect to authority that commands respect, whereas. the response to the kerygmatic preaching is an existential adherence of the whole person to the tidings of salvation” (116).

The Sacramental Model shows that “religious communication occurs not only through words but equally through persons and events (Dei Verbum, 2). Christ himself is seen as the supreme revelatory symbol -- the living image through whom renders make God in some way visible. Christ not only communicates by what he says but even more by what he is and does…” Here, also the Church is seen as an efficacious sign or sacrament in which Christ continues to be present and active. The Church is sign and instrument of the living presence of Christ. The communicative dimension of the liturgy is considered and the “sacramental mode of communication” where “sacred signs produce their saving effect thanks to the power of Christ.” (117)

The Communion or Community Model of the communicating Church is the ‘koinonia,” the “fellowship of life, charity and truth (Lumen Gentium 9) animated by the Holy Spirit.” An expression of this approach is the second chapter of the Vatican II document on the Church Lumen Gentium (9-17) under the heading “The People of God.” This communion model “favors common witness and dialogue” also with other Christians. It probably must be extended even beyond Christianity (cf. LG 16; Nostra Aetate), which leads to the fifth model.

The Secular-Dialogic Model is mainly based on the Vatican II teaching of the Church in the modern world, Gaudium et Spes. Here, the non-Christian world is not simply seen as “raw material for the Church to convert to its own purposes, nor as a mere object of missionary zeal, but as a realm in which the creative and redemptive will of God is mysteriously at work.” (118). Here, the dialogue of the Church with cultures and the world of religions finds its place as well as the dialogue with the growing world of communication which Pope John Paul II lists in his encyclical letter Redemptoris Missio (1990) as “the first Areopagus (marketplace) of the modern age.” (37c) In this model, the Church must interpret the signs of the times (cf. GS 11, 14) and this is considered a special challenge for the Laity (cf. GS 43, 62). This is also confirmed by the Apostolic Exhortation Christifideles Laici (1988). According to Dulles, this “secular-dialogic theology…has repercussions on the kind of dialogue that takes place within the Church.” (120) It also proves that revelation “does not begin with scripture and tradition, or even with Jesus Christ, but with the Word in whom all things have been created. Grace is presumed to operate in the whole of human history. The Church, though it is privileged to know God’s supreme self-disclosure in its Incarnate Son, can continually deepen this grasp of the Divine by dialogue with other religious traditions and by interpreting the signs of the times.” (121) The Pastoral Instruction Communio et Progressio spells the implications of this model out in seeing the contemporary world as a “great round table,” where “a worldwide community is being formed through an exchange of information and cooperation.” (1971, 97, 98)

These models, derived from the different Vatican II documents, are not exclusive but rather complement each other. It depends on a given context. local needs, special initiatives, and visions, just which of them will be more important in a specific situation, country, and continent. For the Church in Asia, the Secular-Dialogic Model plays an important role and must be considered and developed in a special way. Here, the FABC speak of a “Triple dialogue”: 1. People/Poor, 2. Cultures and 3. Religions.

Conclusion

These considerations show how Communication Theology considers the whole of Salvation and Theology under the perspective of Communication. The communicating Trinitarian God ‘speaks’ through creation, his creatures, and he lovingly communicates with them in grace. In His ‘Word’ becoming Flesh, He even becomes part of humans in sharing Himself through Jesus Christ. It is the mission of the Church to continue this sending and Incarnation into the here and now of every time. As a result, for the practice and development of communication of the Church, every Christian must be, first and foremost, a communicating person with an open mind and not be afraid to accept new technological developments.

The late Pope John Paul II reminded us of this in the very last Pastoral Letter of his Pontificate (Il Rapido Sviluppo, 2005), urging us to be unafraid of a contradicting world and unafraid of our own limitations. A real Christian reflects the lovingly communicating God wherever s/he goes. Communication is at the root and essence of Christianity and therefore not just one activity in addition to others. It is, finally, the spirit of Communication Theology which is our special contribution to a global communication society which develops rapidly in a world without any distance anymore.

We are rapidly growing into a total communication society, where everybody can be reached everywhere at any time. Thus, we must especially reflect the essentials of a Christian Communication Theology in our daily lives.

Bibliography

Avery Dulles:

“The Church and Communications: Vatican II and beyond” in: Reshaping Catholicism. Current Challenges in the Theology of the Church. San Francisco (Harper and Row) 1984

The Craft of Theology. From Symbol to System. Dublin (Gill and Macmillan) 1996

Franz-Josef Eilers:

Communicating in Community. An Introduction to Social Communication. Third Edition. Manila (Logos) 2002

Communicating in Ministry and Mission. An Introduction to Pastoral and Evangelizing Communication. Second Edition. Manila (Logos) 2004

Gisbert Greshake:

An den Drei-einen Gott glauben. Ein Schluessel zum Verstehen. 2. Edition. Freiburg (Herder) 1999

“Der Ursprung der Kommunikationsidee” in: Communicatio Socialis, Internationale Zeitschrift fuer Kommunikation in Religion, Kirche und Gesellschaft. Vol. 35, 2002 p.5-26. Mainz (Gruenewald)

Berhard Haering:

Free and faithful in Christ. Moral Theology for Priests and Laity. Vol. II: The Truth will set you free. London (St. Paul) 1979

Peter Henrici:

Ueberlegungen zu einer Theologie der Kommunikation in: Seminarium, New Series vol. XXVI, No. 4, Roma 1986, pp.791-804

Carlo Martini:

“Ephata, Apriti”, Lettera per il Programma Pastorale‚ Communicare’. Milan 1990 (Centro Ambrosiano). English Edition: Communicating Christ to the World. Kansas City (Sheed &Ward) 1994; Philippine Edition Manila 1996 (Claretians). (Translations in this paper from the Italian Original!)

Karl Rahner:

“Selbstmitteilung Gottes” in: Sacramentum Mundi. Vol. IV. Freiburg (Herder) 1969 col. 521-526.

Juergen Werbick:

“Kommunikation: fundamental-theologisch” in Walter Kasper (Ed.) Lexikon fuer Theologie und Kirche. Band 6, Freiburg (Herder) 1997.